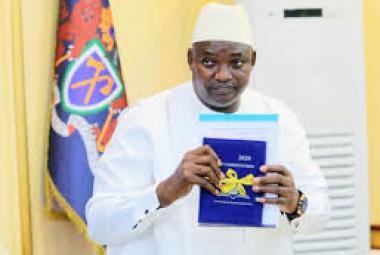

Justice Cherno Sulayman Jallow QC (JSC) made the remarks on Friday at the CRC conference room in Kotu on the occasion of the publication of the proposed draft Constitution.

“These expectations were clearly manifested during the face-to-face dialogue with our people; these were equally manifested in the written submissions we received, including in the other consultation platforms used by the CRC. It was only legitimate that the people had such high expectations. Our job at the CRC, in addition to listening and recording their views and aspirations, was to manage the expectations. We’ve made it very clear in all our public consultations,” Justice C S Jallow said.

The CRC boss explained that the preamble of the current Constitution embody elements considered fundamental including placing emphasis on the respect for the rule of law and fundamental rights and freedoms. It also places emphasis on good governance, separation of powers, sustainable environment and equitable distribution and use of resources, and equality before the law.

He highlighted that the CRC found the opinions expressed by the general public to be very illuminating and referenced real issues. Some were of a constitutional nature while others were of a statutory nature. Others related to issues of policy and clear failures of implementation of existing laws but “our remit is to deal with constitutional law issues.”

“However, our report which will accompany the final draft of the new Constitution will, where considered appropriate, reference the non-constitutional issues that have been raised so that the authorities concerned become aware of them (if they’re not already) and hopefully take necessary steps to address the people’s concerns,” Justice Jallow noted.

As already noted, one of the guiding principles for the CRC under the CRC Act is to ‘seek public opinion and take into account such proposals as it considers appropriate.’ On the one hand, the CRC is expected to consult with and consider public opinion. It is also expected to factor into the draft Constitution such opinions that are considered appropriate. Ordinarily, this is not always the easiest to do. In Gambia’s case, the burden has been lightened by the multiplicity of excellent ideas received from the public.

He explained that in reviewing the current Constitution, they also have an obligation to consider international treaties that The Gambia is a party to and. Furthermore, they have to consider what constitutes international best practice in relation to certain specific subject matters with an obligation to ‘adhere to national values and ethos’ as provided in Section 6 (2) (c) of the CRC Act.

“The end result of taking all these elements into account is that what may, in certain cases, constitute public opinion may not necessarily translate into a constitutional text; yet, on the other hand, what constitutes international best practice may not necessarily become a constitutional requirement if, all things considered, it does not represent the ‘national values and ethos’ of The Gambia. I say these things simply to make the point that we have thoroughly considered all the relevant variables in arriving at decisions with respect to the draft,” Justice Jallow explained.

Justice Jallow further explained that the draft Constitution comprises 20 chapters (3 chapters less than what is contained in the current Constitution); it has a total of 315 clauses. He noted that they have come to the conclusion that while a leaner Constitution may be desirable, it ought not to be the yardstick by which to measure the strength and effectiveness of the Constitution.

He said it was taken into account that as a young democracy with not so strong institutions - one of the things they have attempted to rectify in the draft Constitution - and the need to ensure clarity. Many of the recent constitutions considered, especially those in Africa, have chosen the path of strengthening democratic governance with a good measure of clarity.

“We, therefore, have the option of taking the approach of a leaner Constitution that leaves much to statutory development and legal interpretation or concentrating on teasing out issues that are fundamental to the development of our young democracy, irrespective of the size of the Constitution. We have equally considered the general public opinion canvassed with the CRC, especially by our rural communities, to have a Constitution that is crafted in simple language and easier to read and understand. In this context, we have chosen the latter approach, shying away from the ‘danger’ of leaving too much of too many fundamental issues to interpretation,” the CRC Chairman stated.

By Awa Sowe